Consent apps: yes or no?

I recently came across an interesting article published by The UK Telegraph that exposed a rise in something called “consent apps.” As ridiculous as it sounds, it actually does exist. According to Helena Horton, the author of “Rise of ‘consent apps’ as millennials sign digital contracts before they have sex,” these devices ask users to confirm they give consent to any sexual activity with another user by literally signing or tapping on the screen of the smartphone.

Instead of the traditional motto “no means no,” these apps changed the motto to “yes means yes”– joining the efforts of sexual assault awareness movements like #MeToo and #TimesUp to further promote the idea of affirmative consent, which would give clear and ongoing verbal approval for any intimate or sexual activity.

Curious, I decided to explore this new phenomenon on my trusty iPhone. Within minutes of putting “legal consent apps” in the search bar, I came across multiple apps such as WeConsent, uConsent, or LegalFling. These apps were described like literal legal contracts that bind two users to the agreement. It also promises to provide detailed records in the event of disputes or disagreement about any agreement given for sexual activities, including which specific acts were consented to.

As a means to promote safe, consensual sex, LegalFling allow users to physically approve certain acts. Above is a screenshot of LegalFling’s advertisement on their website.

I downloaded the app “uConsent” on my and my sister’s phones to give it a try. The app was pretty direct and easy to follow– all you needed was a person to type the requested act into the app and another person would type into their phone what they agree to. This generates a barcode the app would capture to “ensure what was requested matches the permissions granted,” sort of like adding a friend on Snapchat. The app automatically stores this information by encrypting it and putting it into a “cloud-based database.”

It sounds simple and it is simple — but because so, it got me questioning whether or not it was as effective as it claims to be. Each intimate situation is different and a simple yes or no isn’t always going to suffice. For example, what if the party was drunk and wasn’t in the right mindset? If a party wants to immediately withdraw consent for whatever reason in the middle of the situation, is there a panic button?

With these issues in mind, I took to the school community to find out what people think of this charade. Some people believed that it may actually reduce sexual assault as the app claimed.

“I think it has the potential to limit sexual assault because everyone will understand what everybody wants,” Marty Kelty, senior, said. “But I think you don’t have to use it if you don’t want to.”

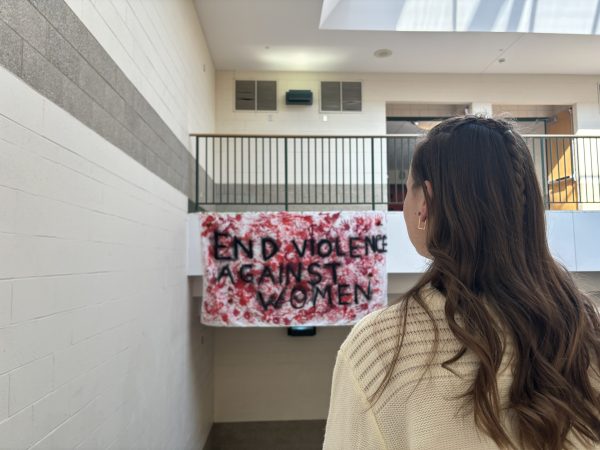

Others seemed skeptical of these apps, claiming that they don’t understand why it’s so hard for people to understand the concept of consent to the point where an app is necessary. One of whom is the sponsor of Empower, a club that focuses on gender inequality.

“What I find concerning is that people are not recognizing how to work with each other socially. If somebody is in an intimate relationship, that’s a really important skill to have — to be able to communicate verbally,” Mrs. DiTomasso, sponsor of Empower, said. “However I do see how in a court of law it might eliminate the he-said-she-said sort of thing, which is what makes sexual assault messy in terms of prosecution.”

Other issues that arise with these apps also concern privacy. For one, many of them don’t require users to log in with their own personal information. And just like using cookies in your normal browser (which are web servers that pass your web browser, which stores your message in a small file called cookie.txt, when you visit certain sites), other apps have access to the user’s contract and personal information because the data are stored in a cloud.

“I don’t think it’s going to catch on but it is a great idea–especially legally, there’s a lot less murkiness to it. But what I find is that it’s a central, emotional, in the moment act and there’s an attribute that’s taken away when it’s binding, like it is on the app,” Matt Keovan, senior, explained. “I think whatever benefit that comes about from it is sort of mitigated just because the user base has to be there, and if people aren’t using it, what’s the point?”

While most people seem unsure about these consent apps, I will point out that it is taking steps toward an issue that needs an imminent solution. But in all honesty, we don’t need an app to tell us what we can or can’t do. What we need is respect for each other and ourselves.

Of course, if we really do need a reminder of what consent is– below is a video link I’ve attached from the recent Erin’s law presentation about consent. I hope that’ll clear up any confusion.

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZwvrxVavnQ

eyHoney Tey is a senior and this her first year on staff. Besides being a Business and Production Manager for York-Hi, she is the Captain of York's Mock...