The real college admissions scandal: disparity

May 10, 2019

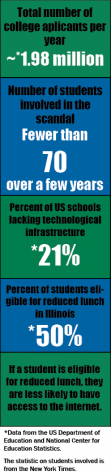

Over the past few months, just as seniors began receiving admission letters from colleges, news organizations broke a high-profile cheating scandal involving bribery, lying about athletics and cheating on standardized tests. These findings have brought charges upon former athletic coaches, administration officials and several parents for their roles in the scandal. These criminal indictments, and the overall scandal, have caused many to become frustrated with the admissions process.

“The scandal makes me angry because college admissions should be based on the skills and hard work students put into their academic or athletic goals,” said senior Will Philips, who will be attending Northwestern University next year. “Bribing admissions officers and prestigious schools to accept students, some of whom lack the motivation and knowledge to make use of the many opportunities provided by the college, is a waste of resources that could be better used on students who would appreciate and take advantage of the opportunity.”

Although the scandal eroded trust in the college admissions process, York college counselor Amy Thompson said the scandal shines light on a reality in college admissions: disparities in the quality of high school education.

“The inequity of the system doesn’t get nearly the attention as the sensational story,” Thompson said. “We’re very fortunate. If you go to York High School, you live in an area with a really good public high school. Not everyone has that. Colleges try really hard to balance that, but they still have to answer to their average GPAs and average test scores. So it puts those in the less resourced schools at a disadvantage purely because of where they live.”

As many public schools obtain funding through local taxes, this links high performing schools with higher income neighborhoods and underperforming schools with lower income neighborhoods. Disparities resulting from unequal school funding can significantly impact the quality of a child’s education.

“There are kids in inner city schools and in rural communities who are working really hard, doing the best they can given the resources they have,” Thompson said. “But many will not ha ve those same opportunities [of York students.]”

ve those same opportunities [of York students.]”

Therefore, many college counselors argue that disparity is the real scandal in this situation; it affects millions of students while this specific scandal only affects a few.

To put it in perspective, Georgetown University, one of the smaller population schools implicated in the scandal, has an undergraduate population of under 8,000 students. This scandal has not implicated more than 70 students. Even if all of the implicated students were going to Georgetown at the same time, which is not the case, they would make up less than 1% of the undergraduate population. So, the chances that the specific scandal impacted a student’s admission to a university are very slim.

“Some of [the students involved in the scandal] definitely would not have been [admitted],” Thompson said. “Nonetheless, there are about 70 kids in all over several years. That’s a drop in the bucket. It’s practically nothing in the number of students going to college each year, even highly selective colleges over a span of a few years.”

The “drop in the bucket” is miniscule in comparison to the number of students attending underperforming schools and needing assistance. For example in the city of Chicago, 75 percent of students attending underperforming schools are on free and reduced lunches in comparison with 15 percent of York students who are on the free and reduced lunches program. These students are also more likely to live in a household that lacks internet access. Therefore due to the high cost of luxuries such as tutoring, which can cost upwards of 60 dollars per session, families who can’t afford lunches will most likely be unable to afford extra help they may need. With the inability to have academic advantages, lower income students are at a major disadvantage in regards to not only test scores, but course work too.

Therefore, disparities in secondary education impact admissions far more substantially than a few individuals cheating on a test or lying about their athletic abilities.