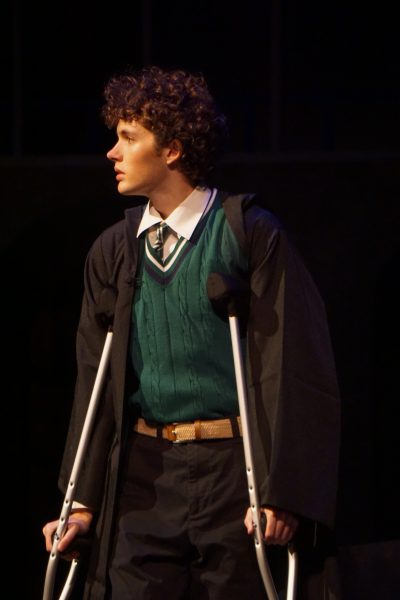

The best chapter of Harry Potter: The Prisoner of Azkaban

For anyone who has read and enjoyed the Harry Potter series in its entirety, deciding which book (or movie) should be esteemed as the best of them all is a popular query. In my experience, The Goblet of Fire, or perhaps The Chamber of Secrets, is ranked first among many. At first glance, I would agree — they have action and a constant suspense in regards to what will happen next that makes it not only a worthwhile read, as all novels by J.K. Rowling are, but an easy one.

However, I think the title of “best” has to be earned in more ways than one — an esteemed actor is not awarded an Oscar for being able to portray only one emotion, just as a book shouldn’t be ranked first among seven in a reader’s mind based on only one aspect, even if that aspect seems to overshadow any other elements of a story. In my opinion, plot is the most prominent characteristic of a story, followed by characters and then setting. But when the setting and characters maintain a certain constancy–as series tend to allow for–the plot becomes much more complex.

Allow me to explain: in a single book, the plot is just that–a plot. There are no sequels or prequels to add to the existing storyline, so whatever is in that single book stands alone. So when judging a book such as To Kill a Mockingbird or The Count of Monte Cristo, the evaluation of a plot is simple, since there is nothing else but the events in that book, and that book alone, to take into account. A series, however, presents a plethora of complications for a seemingly simple rating system. Not only does one have to determine if the book is enjoyable in itself, but its place within the entire series has to be analyzed. In a situation where there is a prequel and sequel, the comparison of how the two stories would stand alone tends to be a big factor. In a long series with a long, complicated plot and an extensive amount of details and backstory, a single book seems to play a much bigger role than just advancing the story– it advances the entire environment.

This is why I simply don’t agree with the fact that the fast-paced Goblet of Fire would be the best of the Harry Potter book, or the edge-of-your seat Chamber of Secrets. When looking at the hero-villain relationship, character development, and critical background story development, the book that is undeniably the best is The Prisoner of Azkaban.

Let’s look at the Prisoner of Azkaban (POA) at face value to start. POA has just as much action as any other book in the series. With the introduction of Sirius Black, an infamous serial killer, right at the beginning, Rowling was able to add an air of suspense throughout the entire novel, since the reader has no idea when or where Black will show up. This keeps the reader hooked, especially once it’s revealed that Sirius Black was actually a good guy. The story then came to be about the strive for justice, which in itself is an appealing storyline.

But what’s most intriguing and fantastic about this book is the newly introduced complexities of relationships; the Wizarding world becomes much more gray.

The relationships between the protagonists is the first indicator of the blurring between right and wrong. Throughout the first two books of the series, the only serious contention that had existed between the characters was between Hermione and the already established pairing of Harry and Ron. That, however, is solved within the first few chapters the heroes are at Hogwarts. POA is the first book where a conflict splits the friend group apart; the boys were mad at Hermione for a considerable amount of the book, the hostility peaking when Hermione got Harry’s broom confiscated for fear that it was jinxed by Sirius Black. This contention, though inevitable in terms of having a group of friends be the protagonists of a novel, shows that their relationship is fallible–it’s not a guarantee. The heroes won’t always be there, as the naive approach in the first two books might have the readers thinking. Friends–even heroes–can turn on each other, which actually turns out to be a major theme in the book as well as the series as a whole.

POA is also the first time where you learn the complexities of Harry’s background–particularly why he is the way he is. Many fans might use a similar reason for why The Chamber of Secrets is superior, but the major difference is in the comparison of the importance of the hero’s and villain’s backgrounds. Don’t get me wrong, both are important and extremely interesting topics to expound on within a story, but the key differences lie in the general traits of each archetype: a villain is always created, but a hero doesn’t have to be.

A villain is created, whether it’s in real life or a fictional universe. Most serial killers in today’s world were abused as children, which led to their divergent behavior as adults. Voldemort follows the same trend: orphaned as a child, with only the knowledge that one of his parents was an incompetent witch and his disowning father was a filthy muggle. No one like Voldemort could possibly be born–he had a lot of anger towards the world, which drove him to destroy it.

Heroism, on the other hand, is ambiguous. There are people like Abraham Lincoln, who brought themselves from the bottom in order to make a positive difference. But then there are people like Heracles, a famous Greek demigod who Zeus conceived that his sole purpose in life was to help the gods defeat the giants, who were born into the hero role. The degree to which a hero creates themselves allows for some freedom when it comes to developing the backstory of a hero; the hero could’ve started from anywhere, and that affects how they react to certain things, how they form relationships with others, what they value, and so on.

The POA focused on the circumstances that led to the event that made Harry a hero in the public’s eye. It brought up the circumstances in detail that led to his defeat of Voldemort, which was the premise of the entire series. Harry’s heroism, though, was neither completely created nor was he completely born with it. This book shows that Voldemort was actually looking for the Potters specifically which means there was something special about them that posed a threat to Voldemort, and that threat ended up being Harry himself. So, in this sense, Harry was born to harm Voldemort, but almost everything he did in Hogwarts was possible due to his own drive and talent, which he developed himself. Harry fell in between the two extremes, and POA was the first time we got a glimpse of it.

The circumstances that led to Harry’s death were important for two reasons: it showed that his parents’ death wasn’t supposed to happen, and that it happened because a friend betrayed them. Peter Pettigrew (better known as Wormtail), was James Potter’s friend at Hogwarts, and had seemed to be right up until the moment Voldemort broke into the Potter home. He was also their Secret Keeper, as Dumbledore believed no one would suspect that he would be chosen over a closer friend, like Black or Lupin. He was considered a friend, a good guy, until Sirius Black, who had suffered the consequences of Wormtail’s betrayal, had his name cleared. This showed that being good or being bad isn’t completely distinguishable: as Voldemort said, there is no good and evil–only power, and those too weak to seek it. That was said in The Sorcerer’s Stone, but the POA brought it to life and showed how relevant it truly was. It also gave Harry a drive to fight against his parents’ murderers; the murder was no longer just a fact of life to be accepted and dealt with quietly, but a burning fire that would motivate him throughout the entire rest of the series.

The introduction of two of James’ friends, Black and Lupin, as well as the groups on Marauder’s Map, connected Harry more to his father and allowed the reader to see that Hogwarts would be a character in itself (of course, Hogwarts’ history was repeatedly brought up, and was the main point in the Chamber of Secrets, but that’s not important). Harry was just a piece in this constantly changing and evolving world, and allowed the reader to have a macroscopic view of the Wizarding world.

Also, there was Remus Lupin. Besides being probably the best character in the entire book, Lupin welded different areas of the magical world together. Prior to his introduction, creatures had been considered inhuman and beastly–unfit for participation in normal society. But Lupin challenged that prenotion that most likely existed in the mind of the reader by being the best Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher, and proving that a werewolf can be docile and even become friends with normal wizards.

I could go on and on about the different complexities and implications of relationships and justice (don’t get me started on justice, that could be another paper) that were introduced in this novel, but it’s clear that POA has introductions and explanations that are unmatched by the other books in terms of establishing Harry Potter as one of the best series on the market. If you still want to say that your favorite is the Goblet of Fire, go ahead, but saying it’s best is an argument you cannot win; a good plot can be found anywhere in the series, but the turning point into the darkness of the Wizarding world can’t be found anywhere else.

Gracie is a junior at York, in her second year on the York Hi staff as the Graphics Editor. She spends a majority of her time drawing, and on extracurriculars...