One size doesn’t fit all; it’s time for a change in York’s dress code

The dress code has always been subject to scrutiny from students; the last thing any high schooler wants is to be controlled. Every student has their own personal fashion, and teenagers are known for testing the boundaries set forth by the administrators and campus supervisors.

Although dress code violations are more common during warmer months, many York students complain regularly about inconsistencies in the policy and its enforcement.

With this in mind the York-hi believes it is time to explore the issues and build on a conversation that has begun among students and administrators.

The Student Handbook states that students are required to have their backs, sides, shoulders, legs, and midriffs “adequately” covered.

The trouble is, the word “adequate” is interpreted differently by students and administrators, and even from student to student.

According to Ms. Smith, Principal, the seemingly vague language was purposeful.

“We [use “adequate”] so that we can, every year, based on the [current] styles, try to use some good common sense about what’s appropriate,” said Smith.

So, it’s actually intended to help students.

Indeed, attempts to set absolute guidelines have proven to be problematic–for intsance, consider the fingertip rule.

As senior Ella DiGregorio, who’s currently working on a project to revise the York’s dress code, discovered, the overwhelming majority of shorts sold for girls today are very short–too short to abide by the fingertip rule.

She presented her findings to the administration, and they listened.

“We’re not going after shorts in the same way [we used to],” said Smith. “It’s just impossible. That’s what’s in the stores; that’s what girls are buying.”

Not only do current styles create a problem, varying body types can pose challenges with consistency as well. Larger and taller girls at York face a more difficult challenge than others when it comes to appearing “adequately” covered. Two people could be wearing the same exact shorts–or skirt–and, even if they’re each wearing the garment in their rightful size, the larger or taller person will seem to be revealing more skin than the other person

The larger or taller person is more susceptibale to a violation of the dress code–for a garment that someone else may have gotten away with wearing.

Administrators acknowledge this issue.

“I think, to some extent, [what’s appropriate is] in the eye of the beholder,” Smith said. Reasonably, “when you have nine campus supervisors, three deans, and one or two administrators involved in [implementing the dress code], you have some variance.”

So, some might argue: just be safe. Don’t take chances.

But, we’re talking about teens, takers of chances. Plus, if we can’t agree on what “adequate” means, how can we be sure of what “safe” means?

Still, awareness is a good start, but we can’t stop there. What better time than winter when everybody’s bundled up to begin the conversation about the dress code? However, that’s exactly what we wanted to do: begin the conversation.

The York-hi conducted a small survey in November in an attempt to collect some preliminary data. While the results only offer a small sampling from the student body, they do introduce some problematic issues that suggest a bigger problem may exitst.

Out of the 86 surveys returned, 23 students answered “yes” to having been dress-coded some time in school. Students are getting penalized inconsistently for dress code violations, as the results from our survey show, and that weakens the understanding of what is and what is not appropriate for school.

Just under 70 percent of students reported they had been dress-coded for wearing an article of clothing which they had previously worn to school without having been dress-coded. (See Figure 1). This brings us to another problem with the word adequate: the discrepancy in what’s decidedly “school appropriate” indeed causes some students to break the dress code unintentionally.

“The more that you spell out [a rule],” however, “the more it’s open to interpretation,” Smith pointed out.

Still, she acknolwedged that, from a student’s perspective, such a vague word seems subjective.

This problem with interpretation is evident in our survey results for both the students breaking the dress code and the administrators trying to enforce it.

Those students who said they have had different reactions from staff regarding the same item of clothing probably had these different experiences because of conflicting classifications by staff of what’s appropriate.

It depends on who saw it. But how effective is that?

While many students want to do away with the dress code entirely, others find it acceptable as written in the handbook but notice issues with the manner in which it is enforced.

Students reporting blatant discrepancy in their dress-coding experiences may find relief in learning that administrators–those writing the handbook and all of its rules–understand the importance of the manner of interactions between staff and students, even if students sometimes feel that campus supervisors practice their powers a little too loudly.

Speaking over a crowded hallway to get the attention of a student in violation of the dress code “is going to feel very much like [the staff member has] confronted you, and it feels overall hostile,” Smith said.

For students in their third or fourth year at York who notice that some styles which used to be deemed inappropriate are now allowed in school and that some which used to be allowed are no longer, this may lead to thinking the administration is wishy-washy, or–even further away from the truth–trying to get us in trouble.

Frankly, administrators have enough to keep themselves busy; they don’t have the time to search for ways to get students in trouble. Their goal in drawing up a dress code–whether one finds it to be reasonable or not–has always been explicit: to maintain an optimal learning environment free from distractions.

“I think it’s important to know that a dress code is not designed to punish kids, but to create an environment where it’s not distracting,” said Smith.

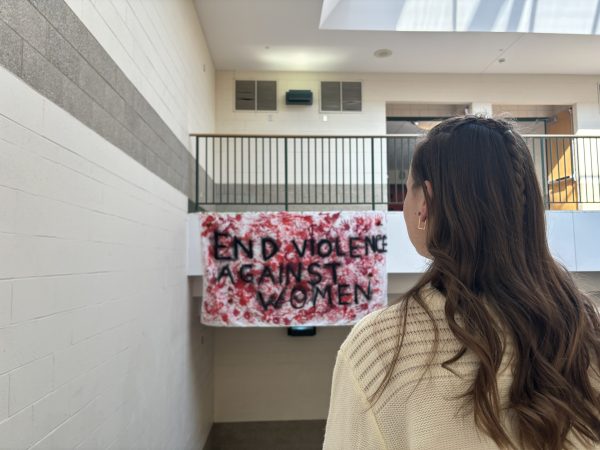

Whereas some see certain clothing pieces as distracting, others see a predominant lack of self-control in those so distracted by someone else’s appearance.

“One of the most important parts that we want to change is that we shouldn’t be teaching girls that they need to cover themselves,” said DiGregorio. Instead, if the administration finds themselves dealing almost entirely with female dress code violations on the basis of clothing revealing too much skin–and if revealing too much skin is problematic because it is “distracting”–then we should look towards the problem we’re trying to minimize: attention deficiency in boys.

A girl’s routine of getting ready in the morning shouldn’t involve having to wonder if a male classmate might get distracted by her outfit.

“We need to be teaching boys to control themselves,” said DiGregorio.

Furthermore, it certainly isn’t acceptable for a boy to do poorly in class because all of his attention resides on his female peers; that’s an attention issue belonging to him, and it’s no fault of the girls.

Still, many girls do walk away from experiences being dress-coded feeling like there’s a fault in their character, not just their fashion choices, even though that’s probably not the intention of dress-code enforcers (See Figure 2).

Forty-three percent of students responded in our survey that they had felt “hurt, or otherwise embarrassed, victimized, or ashamed” after having been confronted by staff for their clothing.

Moreover, many of the body parts prohibited from being exposed are usually exposed on female bodies. Hypothetically, boys could wear clothes exposing too much skin; in reality, the clothing boys wear covers them up. Hypothetically, girls could dress more conservatively; in reality, clothes designed for girls tend to expose some skin.

This losing game has turned the dress code issue at school into appearing more along the lines of a gender bias to some girls, and rightfully so.

Three surveys returned to the York-hi from students who said they had never been dress coded had written on them this additional common statement: “I’m a boy.”

Boys never have to worry about the dress code; a few even said so themselves.

Again this is a small sampling; more data will be gathered in the spring.

Most would agree that we choose to wear what makes us feel good about ourselves. A student’s confidence should not be torn down as a result of these interactions; the dress code may stay, but if part of having a dress code places a responsibility on the staff to discourage or penalize for inappropriate attire, let’s make sure what’s being discouraged is the clothing, not the student. Teenagers might try to act all big and tough, but words can hurt.

York has progressed strongly in the directions of self-acceptance and self-celebration. It’s hard to miss.

We have two clubs dedicated entirely to the empowerment of females and that of sexuality; teachers and administration encourage every student to get involved in a school activity because they want every student to feel at home here; and we hold multiple Arts weeks throughout the year showing off the talent and individuality of our students.

York reflects in countless ways the pride it has in all of its 2,692 Dukes. With that many of us, there will inevitably be drastic differences in appearance. Let’s accept, and let’s celebrate.